4 U.S. Chinatowns You Should Know and Fight For

The Friendship Arch in Chinatown, Washington D.C. Photo credit: Getty Images

If you’ve ever lived in or visited a major U.S. city, this has probably happened to you. You’re walking down the street and—all of a sudden—passersby are speaking Taishanese. You look up to see street signs in Chinese characters and a beautiful decorative arch. It’s time to do a quick Google Maps check or to text your friends to let them know you’ve arrived in Chinatown—one of the unique immigrant enclaves found in cities across the United States. However, we often forget the darker history of how they came to be.

For example, did you know Chinatowns have a long history of providing protection against anti-immigrant violence.

And what about the architecture itself? Did you know Chinatowns were deliberately designed by white architects to appear exotic and appealing to white tourists?

Did you know that over the past 170 years Chinese communities have fought for their continued existence? Chinatowns across the U.S. survive to this day thanks to the strength and resilience of the families that call them home.

From Taishan, China to “Gam Saan”, California

Toy vendor, Chinatown, San Francisco c. 1900s Source: Wikimedia

In 1849, nearly 5,000 Chinese immigrants arrived in San Francisco. A few years later, after a serious crop failure in southern China, the number rose to over 20,000. They were also driven by imperial wars with Britain, poverty, and the promise of economic opportunity in the U.S.

Initially, the newcomers were mostly Chinese migrant workers from Táishān city in Guangdong, China—men who hoped to send money back to their families before eventually returning home to resume their lives. They were initially drawn to “Gām Sāan” to find their fortunes in the 1850 California gold rush. Over time, they opened restaurants, laundries, or found jobs on the transcontinental railroad—where they eventually made up 90% of the Central Pacific Railroad workforce.

As news spread through southern China, the number of immigrants headed to the US increased to 63,000. The majority settled in California.

Racial Violence and the Development of Chinatowns

Chinese prospectors were not the only ones who came to California looking for gold. Between 1848 and 1900, millions of hopefuls participated in the gold rush, including whites, Mexicans—who brought new mining techniques, Natives and Black freedmen from the rural South.

Non-white prospectors did not receive a warm welcome and were viewed as unwanted competition. In 1850, California passed a Foreign Miners Tax of $20/month—worth over $500 in today’s currency—that specifically targeted Chinese and Mexican miners. Some Chinese miners did leave and settled in San Francisco where they helped found the first Chinatown.

The tax was eventually lowered to $4/month. By 1860, Chinese miners had achieved so much success in gold mining operations—despite mostly working claims abandoned by white miners—that they contributed a significant portion of the state and local tax revenues. That year alone, Chinese miners contributed more than $5 million to the State of California through the Foreign Miners Tax—or roughly one-fifth of the state’s revenue in 1860.

“...echoing the uneasiness that Chinatowns have always faced. They are safe spaces that embody a rich cultural heritage. They are protected spaces that embody a rich cultural heritage; whose built environment is designed for outsiders; and whose relative safety has been repeatedly violated by violent acts.”

White miners were not happy.

They felt that, since the U.S. had gained possession of California as a result of the Mexican-American War, the gold being unearthed in the area belonged to whites—not to Black, Native or Mexican miners and certainly not to Chinese immigrants. This racist and xenophobic belief led to violence.

Seeking justice was complicated by a court system that reinforced racial discrimination. An 1854 California Supreme Court ruling prevented Chinese—along with Black and Native residents—from giving testimony against white men. The ruling freed a white man indicted for murdering a Chinese miner, and it was a bad sign of violence to come.

In the 1870s and 1880s, there were 153 anti-Chinese riots across the American West, including in Seattle, Tacoma, and Denver. Chinatowns were emptied, vandalized and set ablaze. Their residents were assaulted, murdered and forced out of town.

From 1871 to 1930, three major anti-Chinese massacres took place across the Western United States in Los Angeles (California), Rock Springs (Wyoming), and Hells Canyon (Oregon). “Chinese catchers” routinely patrolled the American border to chase down America’s first “illegal immigrants”.

In 1882, the U.S. government passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, effectively banning the immigration and naturalization of Chinese laborers. It also prevented family reunification for most of the Chinese laborers already living in the U.S. This was the first race-based immigration policy in the U.S. The initial ten year ban stretched all the way until 1943 and wasn’t fully repealed until 1965. That’s 82 years of family separations.

An 1892 California law required Chinese residents to carry photo identification cards at all times—under threat of deportation and hard labor.

Despite the legal and physical violence directed at their communities, Chinatowns were rebuilt. Over the years they continued to act as safe havens from the intensity of anti-Chinese violence. They became a lifeline for those who had neither the means to return to China nor the ability to become citizens, buy land, marry, have children, go to white schools, live in white neighborhoods or start businesses outside of Chinatown.

1. San Francisco

A San Francisco Chinatown mural brings Journey to the West—one of the greatest classic novels—to life with a Biggie Smalls cameo. Mural by Luke Dragon. Photo by Frederick Wallace on Unsplash

Taiwanese flags decorate the streets of San Francisco’s Chinatown. Photo by Faaizuddin Farooqui on Unsplash

Bounded by Broadway, Kearney, Bush and Powell streets, San Francisco’s Chinatown is most likely the first Chinatown in the United States. In 1848, San Francisco’s Angel Island was also the first port of call for many Chinese immigrants.

Chinese immigrants arriving in San Francisco, faced harassment, intimidation and violence. Yes, San Francisco’s Chinatown offered a safe haven, however, Chinese residents were also legally restricted to it.

In 1890, San Francisco passed a formal ordinance which explicitly stated the following:

[It is] unlawful for any Chinese to reside, or carry on business within the

limits of the city and county of San Francisco, except in that district

of said city and county hereinafter prescribed for their location.

Although a group of immigrants would successfully challenge the constitutionality of the law, Chinese residents would not expand into other parts of San Francisco until well into the 20th century.

Look Tin Eli and the Architecture of San Francisco’s Chinatown

After a 1906 fire destroyed a large portion of San Francisco - including Chinatown - leaders in the community were told by city officials that the old district would never be rebuilt. However, the community fought to rebuild.

Born in Mendocino, California and raised in China, Look Tin Eli became a prosperous merchant and prominent leader in San Francisco’s Chinatown. He was integral to the community’s fight to rebuild Chinatown after the 1906 fire. He also played a role in the use of distinct, “exotic” architecture to rebrand Chinatown as a significant tourist destination.

The architecture—far from being authentically Chinese—was designed by two American Beaux-Arts trained architects, T. Patterson Ross and A.W. Burgen. The architects based the architecture on photographs and etchings taken by early European travelers to China. Although the idea originated in San Francisco, Chinatowns across the country followed suit.

2. Los Angeles

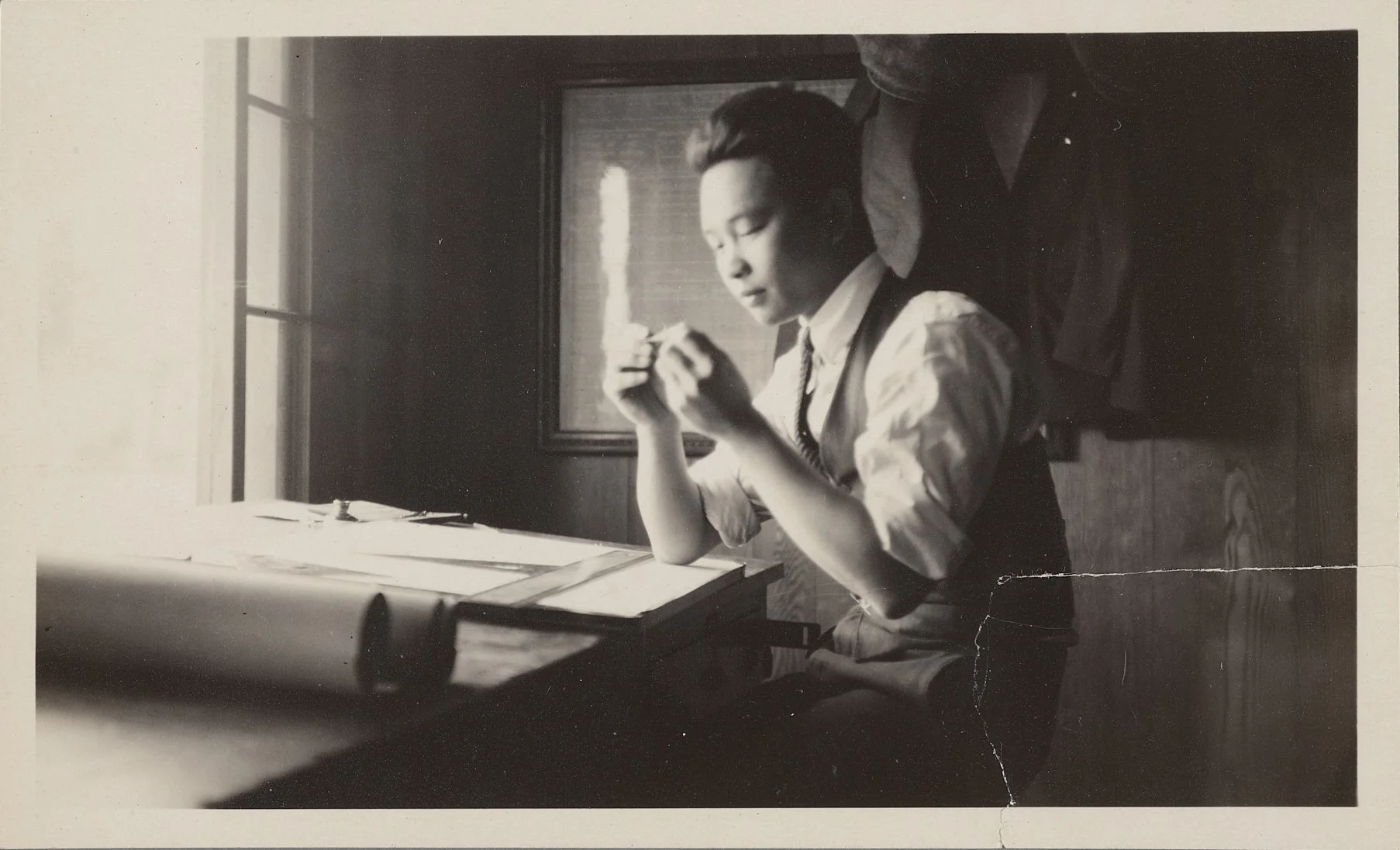

Peter Soo Hoo sits at a drafting table. Source: Huntington Digital Library

Los Angeles Chinatown arch. Photo credit: Getty Images

In 1871, the original Los Angeles Chinatown, was the site of one of the worst anti-Chinese lynchings in United States history. A mob of 500 people destroyed buildings, robbed, assaulted and murdered approximately 18 people of Chinese descent. Although eight people were tried and found guilty for the massacre, all eight convictions were overturned.

Despite the lynchings, Old Chinatown in Los Angeles grew steadily until the early 1920s when the area was leveled to make way for a train station. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the remaining section was razed to make room for Highway 101. Almost nothing remains of Los Angeles’s original Chinatown.

Peter Soo Hoo and the Development of “New Chinatown”

After the Old Chinatown was razed, Peter Soo Hoo, a young engineer and the first Chinese American employee of the Department of Water and Power, identified a promising site owned by the Santa Fe railway. He obtained the financial backing of 28 prominent Chinese civic leaders and businessmen. However, due to the 1913 “alien land laws” which restricted people “ineligible for citizenship” from purchasing agricultural land, Soo Hoo brokered the deal through white Santa Fe Railroad agent, Herbert Lapha.

Soo Hoo’s efforts were vital to the re-establishment of a new Chinatown in 1938. Sixty seven years after mob violence destroyed L.A.’s first Chinatown, the children and grandchildren of the Los Angelenos who lynched and burned were likely among the visitors who came to admire the new decorative arch, dine, shop and marvel at the 1,000-ft golden dragon during the Autumn Moon Festival—echoing the uneasiness that Chinatowns have always faced. They are protected spaces that embody a rich cultural heritage; whose built environment is designed for outsiders; and whose relative safety has been repeatedly violated by violent acts.

3. Chicago

Photo by Aric Cheng on Unsplash

Photo by Lauren Vanden Bosch on Unsplash

Chicago’s original Chinatown was established in the late 1800s by Chinese immigrants fleeing racial violence in the rural Mountain West. Its boundaries ran along Clark Street between Harrison and Van Buren streets. The first neighborhood businesses were a hand laundry and grocery store.

Over time, rising rents and discrimination led the community to move just south of downtown near Cermak Road and Wentworth Avenue which some credit for its continued growth. Instead of being squeezed by land developers or constantly under threat of gentrification, it continues to flourish with affordable rent, new businesses, and community based organizations. Unlike other Chinatowns, it “more than doubled its Chinese population between 1990 and 2020”.

Ping Tom and the expansion of Chicago’s Chinatown

Ping Tom was an influential Chicago-born Chinese American businessman, lawyer and civic leader born in 1935. Outside of his family’s businesses, his greatest achievement was overseeing a “$100 million residential and commercial expansion of Chinatown” as president of the Chinese American Development Corporation. Although he did not survive to see it completed, a park which now bears his name is also situated on 17 acres of land nearby.

Today, Chicago’s Chinatown has a decorative arch built in 1975. Then there’s the Pui Tak Center building, designed by Norwegian architects in 1926, “with its pagoda-inspired towers, green clay roof tiles, and terra-cotta panels”. Tourists also flock to see the Nine Dragon Wall, an impressive glazed tile mural depicting nine large dragons and over 500 smaller ones. Nearby is Chinatown Square, an outdoor mall with twin pagodas and twelve zodiac statues, designed by white American architect Harry Weese—but only after “the first design by architect Y.C. Wong was rejected for being too modern.” Ping Tom Park, a 17 acre recreational area with a pagoda pavilion, bamboo gardens, field houses and more was designed by Ernest C. Wong and constructed in 1999.

Similar to Chinatowns across the country, the Chicago tourism board website uses words like “colorful” and “exotic” to market Chinatown Square as a shopping and dining destination that “transports you straight to eastern Asia.“ That is what outsiders see, however, it leaves out the Coalition for a Better Chinese American Community which provides emergency rent assistance and helps register voters; the Chicago Chinatown Community Foundation which hosts the annual Lunar New Year parade, dragon boat races and a summer fair; the Chicago Chinatown Chamber of Congress which encourage tourism and business growth; along with many churches, temples, language schools, nonprofits and civic groups.

4. New York

Two older adults enjoy a game of xiang qi. Photo by Arthur Osipyan on Unsplash

Chinatown, New York City. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Although the West Coast saw the first Chinatowns emerge, anti-Chinese violence continued to push Chinese immigrants east. By 1923, around 45% of Chinese people residing in the United States lived in major East Coast cities like New York, Boston and Washington, D.C.

The area in Manhattan known as “Chinatown” is defined by the three streets which formed its initial core - Mott, Pell and Doyers. From 1880 until 1965, when race-based immigration policies were finally repealed, the borders of New York’s Chinatown remained firmly fixed. Between 1965 and 2000, Chinatown grew exponentially with the arrival of immigrants from Hong Kong, Fujian and Vietnam. Additional Chinatowns emerged in other locales within the five boroughs. Elmhurst , Flushing - Queens - Sunset Park and Bensonhurst (Brooklyn).

The New York tourism board website describes Chinatown as a “home to a dense population of Asian immigrants.” The word ‘exotic’ is nowhere to be found. Instead, alongside daytrip itineraries and food and drink recommendations, there are blog articles about organizations like Heart of Dinner, which delivers hot meals and groceries to older residents.

Yin Kong, Jan Lee and a New Generation of Leaders in Chinatown

Across the five boroughs, working-class ethnic enclaves are facing immense pressure from gentrification and rising rental prices. Landlords in Chinatown are finding ways to harass tenants in rent-stabilized apartments into leaving as new high-rise developments are built along the waterfront. In 2017, Mayor Bill de Blasio proposed the construction of a 350-foot tall borough-based jail within Chinatown as part of the city’s efforts to close Rikers Island and fix failed incarceration policies.

Leaders like Jan Lee, co-founder of Neighbors United Below Canal (NUBC), vehemently oppose plans for the new jail and other proposals which put Chinatown residents at risk for displacement. Lee cites both pre-existing challenges, such as food insecurity and mental health issues, and the rise of anti-Asian violence during the pandemic as reasons to preserve the centuries-old, tight-knight, densely populated community.

While community leaders like Jan Lee are fighting for the rights of Chinatown residents, other young leaders like Yin Kong, the Director and Co-Founder of Think!Chinatown, are inspired by the neighborhood’s cultural capacity and hope to carry on that tradition well into the future. Think!Chinatown, previously a bar, underwent renovations to become an open art space late last year.

In the face of a 21st century cultural cleansing campaign (also known as gentrification), Chinatowns are once again proving valuable as safe havens and sites of political organizing.

Bibliography

American Experience, PBS. (2017, October 10). Chinese immigrants and the Gold Rush. American Experience | PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/goldrush-chinese-immigrants/

Building communities | Chinese | Immigration and Relocation in U.S. history | Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress. (n.d.). The Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/chinese/building-communities/#:~:text=In%20the%20face%20of%20a,Chinese%20residents%20alike%2Cas%20Chinatowns

Coalition for a Better Chinese American Community. (n.d.). Coalition for a Better Chinese American Community. https://cbcacchicago.org/

CCCF homepage. (n.d.). Chicago Chinatown Community Foundation 芝城華埠基金會. https://www.ccc-foundation.org/

Chinatown Square | BLUEPRINT: Chicago. (2010, August 3). Design Is Copyright 2008 - 2024 the Theme Foundry. https://www.blueprintchicago.org/2010/08/03/chinatown-square/

Chinese massacre at Deep Creek. (n.d.). https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/chinese_massacre_at_deep_creek/

Choose Chicago. (2023, July 18). Chinatown - Chicago Neighborhoods | Choose Chicago. https://www.choosechicago.com/neighborhoods/chinatown/

District, C. P. (2019, August 1). Tom (Ping) Memorial Park | Chicago Park District. https://www.chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks-facilities/tom-ping-memorial-park

Heart of Dinner. (n.d.). Heart of Dinner. https://www.heartofdinner.org/

Goyette, B. (2019b, May 22). How racism created America’s Chinatowns. HuffPost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/american-chinatowns-history_n_6090692

ESJJ: Chinese in America: A Silent Journey and Invisible Existence. (n.d.). https://www.geneseo.edu/~esjj/Fall2005_3.html

Kennedy, L., & Kennedy, L. (2023, April 28). Building the Transcontinental Railroad: How 20,000 Chinese immigrants made it happen. HISTORY. https://www.history.com/news/transcontinental-railroad-chinese-immigrants

Malagón, E. (2023, July 28). Chicago’s flourishing Chinatown means growth for city, Asian Americans - Chicago Sun-Times. Chicago Sun-Times. https://chicago.suntimes.com/2023/7/28/23800756/chinatown-chicago-historic-landmark-district-asian-community

Ohanesian, L. (2023, March 9). How the destruction of LA’s original Chinatown led to the one we have today. LAist. https://laist.com/news/la-history/destruction-las-original-chinatown-led-to-one-we-have-today

Ramesh, S. (2023, July 12). History of San Francisco and the Chinatown. RTF | Rethinking the Future. https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/city-and-architecture/a5029-history-of-san-francisco-and-the-chinatown/

Research Guides: Rock Springs Massacre: Topics in Chronicling America: Introduction. (n.d.). https://guides.loc.gov/chronicling-america-rock-springs-massacre#:~:text=In%20the%20morning%2C%20a%20fight,and%20kill%20approximately%2028%20people.&text=All%20500%20Chinese%20miners%20are,driven%20out%20of%20Rock%20Springs

Sietsema, R. (2016, August 17). The making of Manhattan’s Chinatown | MOFAD City. Eater.com. https://www.eater.com/a/mofad-city-guides/chinatown-nyc-chinese-history

The unlikely boom of Chicago’s Chinatown. (2016, February 22). https://nextcity.org/features/chicago-chinatown-development-small-businesses

Wikipedia contributors. (2024, March 19). Los Angeles Chinese massacre of 1871. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Los_Angeles_Chinese_massacre_of_1871#:~:text=Approximately%20500%20white%20and%20Latino,to%20as%20%22Negro%20Alley%22

Xu, A. (2023, May 22). The New Generation of Chinatown Leaders on the Neighborhood’s Future. Documented. https://documentedny.com/2023/05/22/chinatown-future-leaders-change-generation/

Further Reading

Rohrbough, M. J. (1998). Days of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the American Nation. Western Historical Quarterly, 29(2), 225. https://doi.org/10.2307/971331

Tsui, B. (2010). American Chinatown: a people’s history of five neighborhoods. Choice Reviews Online, 47(10), 47–5865. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.47-5865

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning. Chinatown Community Vision Plan. (2015)

Ngu, S. (2019, September 25). New York’s Chinatown edges out working-class Chinese people who stayed. Vox. https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/2019/9/18/20861446/new-york-city-chinatown-gentrification-lower-east-side

Now that I’m exactly six months post-op from lower back spinal fusion surgery, my workouts are shifting. Initially, I stuck to body weight and light weight resistance to keep pressure off the bone. Now, I’m finally getting back to heavier weights and more of my pre-surgery workouts. So with that my series on spinal fusion recovery comes to end! But don’t despair, I have a few last exercises to share!